Maria Lisa Polegatto - December 2023

Have you ever been stung by a jellyfish or encountered a smack (group) of jellyfish? I have never been stung by one, but my son was when swimming in the Bras D’Or Lakes, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, and the long tentacles attached to his skin and had to be picked off individually very carefully. Some jellyfish stings can be toxic to humans.

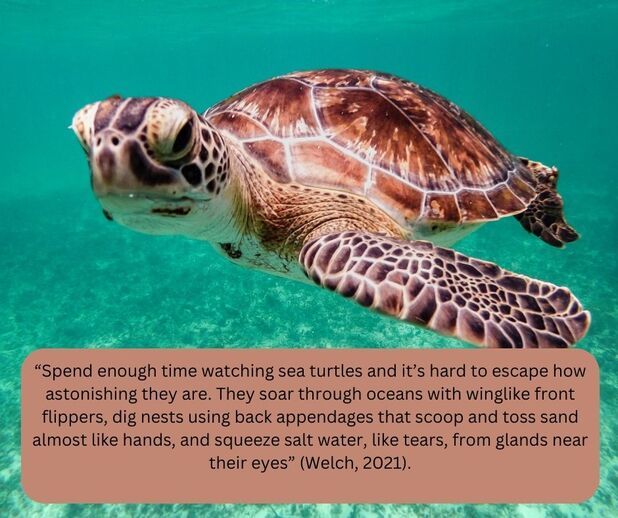

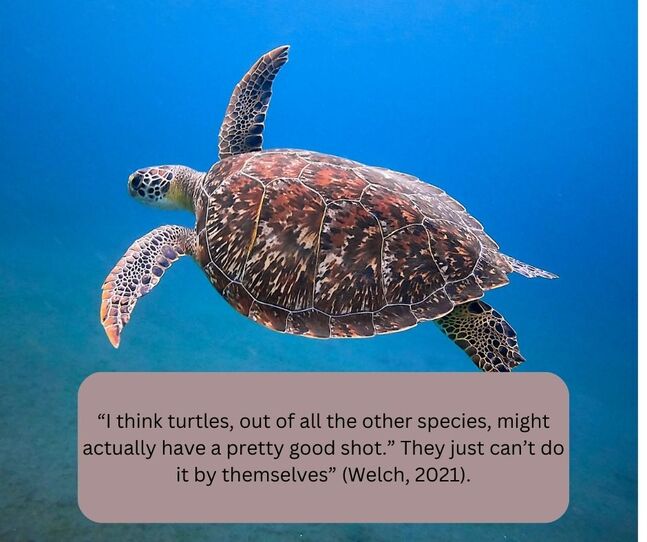

If you spend time at the ocean, you have likely seen many jellyfish but not likely many sea turtles. Sea turtles eat jellyfish, even toxic jellies. Sea turtles can travel globally and chase jellyfish from the southern waters to the north in Canada and then back south when the Canadian waters and weather turns colder. Unfortunately, sometimes sea turtles can get caught in cold water before they return to warm southern waters and can die or become cold stunned (frozen) and appear dead.

Source of Community Vigor

Logo credit: Canadian Sea Turtle Network

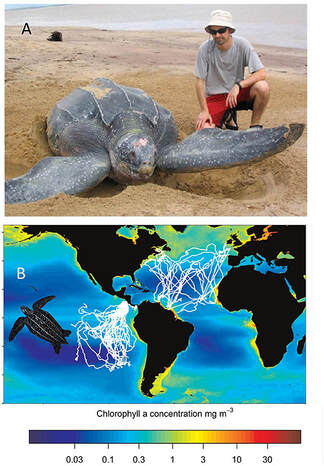

Logo credit: Canadian Sea Turtle Network The Canadian Sea Turtle Network (“CSTN”) is a source of vigor in my community of Atlantic Canada. CSTN is a “charitable organization involving scientists, commercial fishermen, and coastal community members” working since 1998 to “conserve endangered sea turtles in Canadian waters and worldwide” (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). Since Leatherbacks stay in the ocean waters, CSTN performs all their research at sea with marine biologists and fishermen working together collaboratively (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). I like to refer to fishermen as the eyes of the sea since they spend so much time on the water and see in real time any changes.

In summers, CSTN work along the South Shore of Nova Scotia and in Cape Breton making ground-breaking contributions to leatherback science and "morphometirc" data (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). CSTN research has successfully been able to identify many aspects of leatherback turtles, such as:

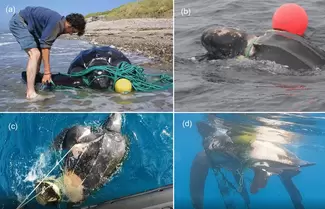

As of November 23, 2023, there were eight (8) “cold-stunned hard shell sea turtles” located “along the NS side of the Bay of Fundy” in nine (9) days, “including "Scottie", a “juvenile green sea turtle” found alive (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2023). Luckily for Scottie, and ultimately the planet, humanity and green sea turtle species, a volunteer found Scottie on the shoreline and called the CSTN Hotline number and Scottie was rescued and sent to Bermuda via air flight to recover and swim in warm waters at the Aquarium Museum and Zoo (Auld, 2023). Every turtle matters. [see article below in further resources about Scottie and pictures below.]

In summers, CSTN work along the South Shore of Nova Scotia and in Cape Breton making ground-breaking contributions to leatherback science and "morphometirc" data (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). CSTN research has successfully been able to identify many aspects of leatherback turtles, such as:

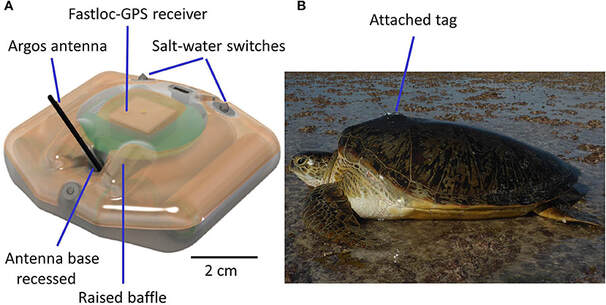

- Atlantic Canada is a critical habitat for leatherback migration evidenced through satellite tracking (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021).

- gathering of “data on male and sub-adult leatherbacks” who live in the sea, unlike females who go to land to nest (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021).

- “Flipper tagging, PIT tagging, satellite telemetry, and DNA analysis were identified” as originating/nesting regions “(~60% from Trinidad; French Guiana and Costa Rica are other major sources)” (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021).

- “Morphometrics and turtle-borne camera work recognized the Atlantic Canada’s jellyfish as a food source for leatherbacks who can eat their body weight in jellyfish every day!” (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021).

As of November 23, 2023, there were eight (8) “cold-stunned hard shell sea turtles” located “along the NS side of the Bay of Fundy” in nine (9) days, “including "Scottie", a “juvenile green sea turtle” found alive (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2023). Luckily for Scottie, and ultimately the planet, humanity and green sea turtle species, a volunteer found Scottie on the shoreline and called the CSTN Hotline number and Scottie was rescued and sent to Bermuda via air flight to recover and swim in warm waters at the Aquarium Museum and Zoo (Auld, 2023). Every turtle matters. [see article below in further resources about Scottie and pictures below.]

Left: "Scottie" found on the shoreline in Canada; Right: Scottie swimming in Bermuda after being rescued

(Credit: Auld, 2023).

(Credit: Auld, 2023).

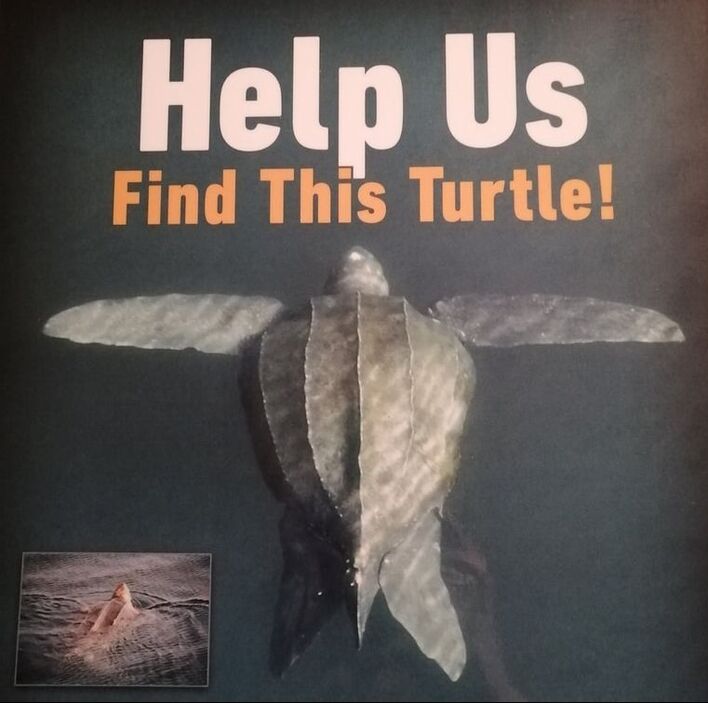

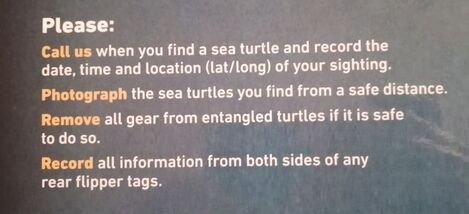

If you see a live or dead sea turtle,

please call CSTN immediately

Toll-free CSTN Sea Turtle Hotline:

1-888-729-4667

24 hours/day, 7 days/week

Credit: Canadian Sea Turtle Network

Species of Sea Turtles

Do you know all the types of sea turtles? Turtles are a keystone species benefitting the ocean ecosystem. With climate change worsening, conservation efforts are vital to turtle species (IUCN, n.d.). The IUCN assessments of turtles range from last completed in 1996 with the most recent assessment in 2019 (IUCN, n.d.). All of the 7 sea turtle species are dangling both regionally and globally (Welch, 2021). Sea turtle nesting takes place on “all continents, except for Antarctica”, where 3 to 5 sea turtle species may use the same beaches, such as in the “Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and Australasia” (Scheelings, 2023). Sea turtle species include

Canadian Sea Turtle Network (2017)

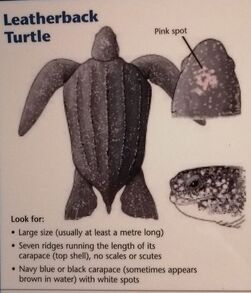

Canadian Sea Turtle Network (2017) Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). This sea turtle species is “more than 150 million years” old, the largest sea turtle and largest reptile globally ranging from “4-8 feet in length (1.2 – 2.4 meters)”, weighing “between 500-2,000 pounds (225-900kg)” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.) outweighing polar bears (Welch, 2021), with the average adult leatherback measuring “between 5-6 feet (1.5-1.8 meters)” and weighing “600-800 pounds (270-360kg)” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.) and “one of the most imperiled” sea turtles (Welch, 2021). They continue to survive despite human interference taking major tolls on their population (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). Leatherbacks can be located “throughout the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans”: in the Pacific, their range exists from the “north in Alaska to southern parts of New Zealand”, and in the Atlantic, they can be located “as far north as Norway and the Arctic Circle and south to the tip of Africa” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.).They mainly wander in open ocean waters but “tend to migrate to tropical regions, such as Trinidad, and subtropical coastal regions to mate and nest” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). Only limited “large juvenile or adult leatherback turtles” arrive in the “Mediterranean from the Atlantic (Casale, 2011). Global conservation status is vulnerable (Scheelings, 2023).

Canadian Sea Turtle Network (2017)

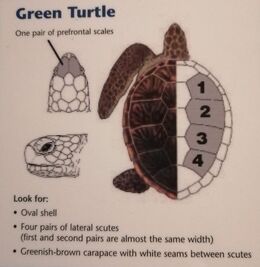

Canadian Sea Turtle Network (2017) Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas). This is the second largest sea turtle weighing “up to 500 pounds (225 kg)” and reaching 4 “feet (1.2 meters) in length”. The adult green turtle “is an herbivore which dines on many forms of marine plant life” with their “sharp, jagged and saw-like” beak, completely “adapted for grazing in sea-grass beds and scraping algae off of hard surfaces” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). This species can be located “in the sub-tropics and tropics worldwide, with major nesting beaches in Tortuguero (Costa Rica), Oman, Florida, Raine Island (Australia), French Frigate Shoals in the North-western Hawaiian Islands, Guam, American Samoa, Suriname, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Puerto Rico, Trinidad and the US Virgin Islands” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). They are often found around “Seagrass beds and Coral reefs by divers” in Trinidad and Tobago (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). Global conservation status is endangered (Scheelings, 2023)

Canadian Sea Turtle Network (2017)

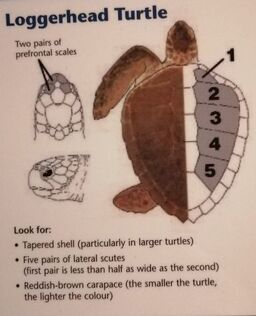

Canadian Sea Turtle Network (2017) Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta). This species “ranges from 200-400 pounds (90-180 kg) and up 4 feet in length (1.2 meters)” and is the most abundant species nesting mostly in “Greece, Turkey, Cyprus and Libya” (Casale, 2011). At sea, they are common in the “area from the Alboran Sea to the Balearic Islands, the Sicily Strait, the Ionian Sea and the wide continental shelves in the north Adriatic, off Tunisia-Libya, off Egypt and off southeast coast of Turkey” (Casale, 2011). Several of these foraging areas are shared with “loggerhead turtles of Atlantic origin”, particularly, “the western Mediterranean, the Sicily Strait, the Tunisian continental shelf and the Ionian Sea” (Casale, 2011). Loggerhead turtles can be found in the United States and have large heads and strong crushing jaws to enable them to “eat hard-shelled prey such as crabs, conchs and whelks” (snails) (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). While loggerheads are located in every ocean globally, their largest intensity of nesting occurs on “Masirah Island off the coast of Oman in the Middle East”, in the Pacific, main “nesting grounds include Japan and Australia, in the “Atlantic the main area occurs in Florida, and they “are the most common species in the Mediterranean, nesting on beaches in Greece, Turkey and Israel” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). Global conservation status is vulnerable (Scheelings, 2023).

Credit: Welch, 2021

Credit: Welch, 2021 Hawksbill Sea Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata). The hawksbill is the “most beautiful of sea turtles for their colourful shells” and is located “in tropical waters around the world” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). Their “diet is very specialized” feeding almost solely on sponges as they “spend their time in coral reefs, rocky areas, lagoons, mangroves, oceanic islands, and shallow coastal areas” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). With “its narrow head and sharp, bird-like beak”, this species “can reach into cracks and crevices of coral reefs” searching for food. This is one of the smallest sea turtles, with adults weighing “between 100-200 pounds (45-90 kg)” and reaching “2-3 feet (roughly 0.5 to 1 meter) in length” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). The species habitats are “tropical and some sub-tropical regions in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans” with most of this population in the “Caribbean Sea, the Seychelles, Indonesia, Mexico, and Australia” with none found in the Mediterranean and only a handful nest in Florida each year (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). Global conservation status is critically endangered (Scheelings, 2023).

Credit: Welch, 2021

Credit: Welch, 2021 Olive Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea). This species “weighs between 75-100 pounds (34-45 kg) and reaches 2-2.5 feet (roughly 0.6 meters) in length”, being named “the Olive Ridley because of their pale green carapace or shell (Natureseekers.org, n.d.).” They nest in large masses referred to as “arribadas and during arribadas, thousands of females nest over the course of a few weeks (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). Adult Olive Ridley species reach their sexual maturity at the age of 15 years (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). Olive Ridley sea turtles can be located globally but their primary habitat is “in tropical regions of the Pacific, Indian and Southern Atlantic Oceans” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). While they prefer open sea life, “they nest on bays and estuaries” in approximately 40 countries, including “Mexico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Australia, parts of Africa, and a few beaches along the coast of India” (Natureseekers.org, n.d.). Global conservation status is vulnerable (Scheelings, 2023).

Credit: Welch, 2021

Credit: Welch, 2021 Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii). This species can live for 50 years and grow to two feet long while weighing 100 pounds being the most globally endangered sea turtle (National Geographic, n.d.). The kemp’s ridley is primarily found in the Gulf of Mexico, but can travel north as far as Nova Scotia, Canada (National Geographic, n.d.). Their upper shell or carapace” is a greenish-grey color, and their bellies are off-white to yellowish” (National Geographic, n.d.). Global conservation status is critically endangered (Scheelings, 2023).

Credit: Welch, 2021

Credit: Welch, 2021 Flatback Sea Turtles (Natator depressus). The flatback sea turtle lives in areas of northern Australia, often remaining in waters less than 50 metres depth (Wilson et al, 2023) with foraging grounds “in the Indonesian archipelago and Papua New Guinea” (van Putten et al, 2023). Global conservation status is data deficient (Scheelings, 2023).

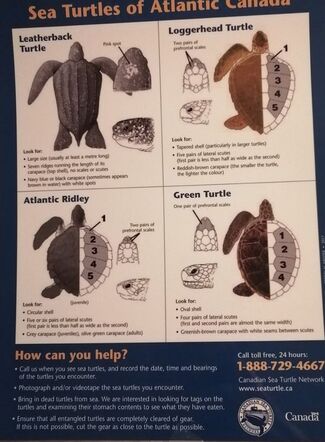

The four (4) sea turtle species found in Atlantic Canada are the

(Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2017)

- Leatherback Sear Turtle

- Loggerhead Sea Turtle

- Atlantic Ridley Sea Turtle

- Green Sea Turtle

(Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2017)

Threats to Sea Turtles

Sea turtles are under a variety of threats globally, including:

- Artificial lighting – Nighttime use of artificial lighting due to increasing coastal development neighbouring nesting beaches effects turtles by limiting the selection of nests of adult females as they prefer darker beaches and it can also disturb the natural direction of hatchlings using light to determine horizon brightness for sea orientation (Kamrowski et al, 2014). With artificial lighting being common globally, reductions can be a challenge with humans lacking natural dark light experience, while also having negative effects to exposure (Kamrowski et al, 2014). With increasing use, the reduction of public night lighting is important (Kamrowski et al, 2014).

- Bycatch in the Mediterranean is a critical “conservation challenge” for global marine megafauna including sea turtle populations (Casale, 2011).

- Climate change due to human impacts (Casale, 2011) such as hurricanes destroying nests and waters flooding nests and drowning sea turtle eggs (Welch, 2021), temperature increases resulting in birthing of female turtles and lower survival rates (Scheelings, 2023).

- Direct exploitation in the Mediterranean due to human impacts (Casale, 2011) such as the consumerism and consumption of sea turtles, including their shells, meat, and eggs (Welch, 2021).

- Fishing gear in the Mediterranean, such as drifting nets, set nets, bottom trawls, pelagic longlines and demersal longlines (Casale, 2011).

- Geographic complex issues (McLean et al, 2023) due to their global marine travel.

- Habitat use and misuse by humans destroying nesting areas (Casale, 2011).

- Human actions that degrade turtle survival rates (Casale, 2011) such as oceanfront subdivisions and hotels taking over beach areas (Welch, 2021).

- Number of countries involved (Casale, 2011).

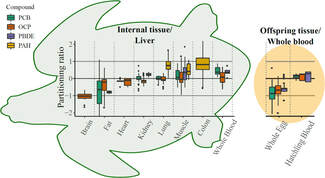

- Pollutions of different varieties (Casale, 2011) such as balloons lodged in sea turtle intestines, plastic straws and forks, spills in waters (Welch, 2021).

- Politically complex issues between countries (McLean et al, 2023).

- Wildlife digging up and eating sea turtle eggs and hatchlings (Welch, 2021).

- Introduced animals (non-native predators) (van Putten et al, 2023).

- Conservation Efforts

Technology and adaptations and modifications to equipment, policies and knowledge can lead to conservation of sea turtle species, including:

For migratory marine species that includes sea turtles, “to be sustainably managed and recover, a coordinated and cross-cultural approach” throughout all related jurisdictions, with all rights holders/stakeholders and relevant worldviews is required (McLean et al, 2023).

- Modifications to fishing gear, fishing operations, fisheries closures, and fisheries increased awareness and education, such as “Turtle Excluder Device”, circle hooks, hooks deeper in waters, trawling tow duration, night-time fishing, identifying areas and seasons (Casale, 2011).

- Motion sensor lighting, use of curtains and blinds, less use of nighttime external lighting and lower brightness of lighting are some options for mitigation of public artificial lighting use near coastal areas (Kamrowski et al, 2014).

- Standardized fishing gar, statistics, datasets, data collection (Casale, 2011).

- “synthesize animal movement data and connectivity information into actionable knowledge” (McLean et al, 2023).

- “Technical characteristics of the gear, target species, turtle size, fishing and social sector” is essential for explaining proper conservation measures for Mediterranean populations of loggerhead and green sea turtles (Casale, 2011).

- Weaving “Indigenous knowledge, practices, innovations, and teachings” encompassing a “place-based knowledge” evolved through “interactions, interpretations, and site-specific connections between the Indigenous people and their Country (or territory)”, through their generations with “biophysical monitoring data” to add to the understanding of “species distribution, abundance, life cycles, threats, and migratory connectivity” (McLean et al, 2023).

- GPS transmitter decoy eggs are put into sea turtle nests to track eggs that are stolen from nesting sites (Welch, 2021).

- Dogs sniffing out sea turtle nests (Brown, 2023).

- Satellite telemetry methods (Wilson et al, 2023).

- Oceanographic circulation models coupled with particle tracking models (Wilson et al, 2023).

For migratory marine species that includes sea turtles, “to be sustainably managed and recover, a coordinated and cross-cultural approach” throughout all related jurisdictions, with all rights holders/stakeholders and relevant worldviews is required (McLean et al, 2023).

Sea Turtle History

“Exploitation of marine resources in the Mediterranean began around 500 BC” while harsh exploitation occurring in the “first half of the 20th century” by the fishery industry that specifically targeted sea turtles “off Palestine and in the Iskenderun Bay in Turkey”, and the sale of sea turtles “to the United Kingdom and Egypt”; however, now international trade is not a conservation issue in the Mediterranean but large numbers of sea turtles are “by-caught by fishing gears targeting other species” (Casale, 2011). There are high magnitude of sea turtle strandings ashore from fishing gear interaction in Egypt, Greece, Italy, Spain (Casale, 2011). In some fisheries, intended killing for meat is linked to incidental captures and consumption by fishermen or “traded at local markets” and intended injuring or killing for other reasons (Casale, 2011).

With sea turtles, including other migratory marine species moving “cyclically and predictably” to achieve their takes across a variety of life-history stages, they travel an array of “jurisdictions, connecting distant locations (e.g. coastal areas to the high seas) through their transboundary journeys (McLean et al, 2023).

This results in many “political and geographically” complexities in “studying, managing, and protecting migratory marine species, their habitats and migratory routes” (McLean et al, 2023). 85% of sea turtles are “listed as Near Threatened or Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)” (McLean et al, 2011). Due to global decline, there is critical need “to synthesize animal movement data and connectivity information into actionable knowledge” for conservation decisions (McLean et al, 2011).

With sea turtles, including other migratory marine species moving “cyclically and predictably” to achieve their takes across a variety of life-history stages, they travel an array of “jurisdictions, connecting distant locations (e.g. coastal areas to the high seas) through their transboundary journeys (McLean et al, 2023).

This results in many “political and geographically” complexities in “studying, managing, and protecting migratory marine species, their habitats and migratory routes” (McLean et al, 2023). 85% of sea turtles are “listed as Near Threatened or Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)” (McLean et al, 2011). Due to global decline, there is critical need “to synthesize animal movement data and connectivity information into actionable knowledge” for conservation decisions (McLean et al, 2011).

Culture

Numerous “aspects of Indigenous culture and knowledge” were lost or harshly impacted by unjust policies and discriminatory colonial processes globally (McLean, et al, 2023). Incorporating Western science and Indigenous knowledge identifies both knowledge systems and offer benefits in unification with each other (McLean et al, 2011). The “intergenerational knowledge” within coastal Indigenous societies surrounding “stock dynamics; sustainable harvesting practices; weather and climatic norms; and tide and current patterns; among others” can “amplify stewardship capacity and augment monitoring programs” (McLean et al, 2023).

Indigenous peoples are custodians of their areas, and are often the first to witness changes, such as declining abundance of species and change to population dynamics (McLean et al, 2023). They are also often the first to be “impacted by anthropogenic, climatic, or environmental shifts” affecting “food security, economies and cultural identities” (McLean et al, 2023). These “coastal communities’ cultures, economies, knowledges, languages, laws, well-being, and worldviews” are deeply linked to the yearly return or movements of migratory marine species and “hold stewardship lores, laws, and management practices for respective places and species” based on the “collective, long-term observational knowledge that have allowed sustainable use of marine resources across millennia” which can be useful to current conservation efforts and contribute to decision-making practices (McLean et al, 2023).

While there is no globally integrated definition for “culturally significant species”, there are identifying features and characteristics that relate to Indigenous communities across Australia and Canada (McLean et al, 2023). Theses species are critical to Indigenous Peoples’ characteristics and central to their connectedness and protection of Country and are explicitly defined by their significance due to their purposeful role or prevalence, including “cultural identity, language, spiritual values, traditions and practices” (McLean, et al, 2023).

For the advantage of preserving cultural connections, identities and supportive developments in marine policy, inspiring more community-led research that: is grounded in Indigenous significances; supports Indigenous rights and tasks for migratory species; upholds expression and continued Indigenous culture and traditional marine resources; includes traditional methods and current technology; expands scientific knowledge and standards for scientifically data deficient species; increases marine connectivity understanding between coastal and offshore waters; gives strength to Indigenous governance systems and protocols for management of resources with and extending Indigenous jurisdiction (including international waters); and decolonizes source management practices, can help improve conservation efforts of transboundary culturally significant species (McLean et al, 2023).. Indigenous knowledge methods are essential to the conservation of all migratory species and related marine ecosystems (McLean et al, 2023).

Indigenous peoples are custodians of their areas, and are often the first to witness changes, such as declining abundance of species and change to population dynamics (McLean et al, 2023). They are also often the first to be “impacted by anthropogenic, climatic, or environmental shifts” affecting “food security, economies and cultural identities” (McLean et al, 2023). These “coastal communities’ cultures, economies, knowledges, languages, laws, well-being, and worldviews” are deeply linked to the yearly return or movements of migratory marine species and “hold stewardship lores, laws, and management practices for respective places and species” based on the “collective, long-term observational knowledge that have allowed sustainable use of marine resources across millennia” which can be useful to current conservation efforts and contribute to decision-making practices (McLean et al, 2023).

While there is no globally integrated definition for “culturally significant species”, there are identifying features and characteristics that relate to Indigenous communities across Australia and Canada (McLean et al, 2023). Theses species are critical to Indigenous Peoples’ characteristics and central to their connectedness and protection of Country and are explicitly defined by their significance due to their purposeful role or prevalence, including “cultural identity, language, spiritual values, traditions and practices” (McLean, et al, 2023).

For the advantage of preserving cultural connections, identities and supportive developments in marine policy, inspiring more community-led research that: is grounded in Indigenous significances; supports Indigenous rights and tasks for migratory species; upholds expression and continued Indigenous culture and traditional marine resources; includes traditional methods and current technology; expands scientific knowledge and standards for scientifically data deficient species; increases marine connectivity understanding between coastal and offshore waters; gives strength to Indigenous governance systems and protocols for management of resources with and extending Indigenous jurisdiction (including international waters); and decolonizes source management practices, can help improve conservation efforts of transboundary culturally significant species (McLean et al, 2023).. Indigenous knowledge methods are essential to the conservation of all migratory species and related marine ecosystems (McLean et al, 2023).

Left: Tilly and Bella (my sea turtle patrol beach assistants) enjoying Belfry, CB, NS; Right: Belfry, CB, NS (Photo credits: Polegatto, M.L.)

A wonderful way to beat consumerism and venture outside into voluntary simplicity is to spend time in nature. I love my time in nature and I love being a CSTN sea turtle beach patroller with my two beach patrol assistants, Tilly and Bella (my dogs).

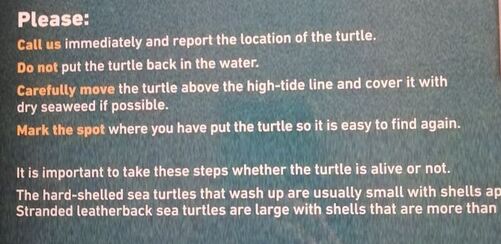

The CSTN sea turtle beach patrol program is a group of volunteers doing citizen science visiting their local beach at least once a week to monitor the coastline at high tide for any turtles that may have washed ashore. While these turtles can be found dead, it is possible they are cold stunned and able to be rehabilitated. The quicker the sea turtles are found, the more chance they have of survival. If you do find a stranded sea turtle, it is important to call the CSTN hotline immediately and report the finding.

Do not attempt to warm up the sea turtle or put it back in the water (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2023). The experts at CSTN will give you instructions on how to proceed.

The CSTN sea turtle beach patrol program is a group of volunteers doing citizen science visiting their local beach at least once a week to monitor the coastline at high tide for any turtles that may have washed ashore. While these turtles can be found dead, it is possible they are cold stunned and able to be rehabilitated. The quicker the sea turtles are found, the more chance they have of survival. If you do find a stranded sea turtle, it is important to call the CSTN hotline immediately and report the finding.

Do not attempt to warm up the sea turtle or put it back in the water (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2023). The experts at CSTN will give you instructions on how to proceed.

Feel free to cocoon in your home while you snuggle up with a blanket and warm cup of your favorite beverage to shop online or donate to CSTN. You can find many wonderful products from clothing to books to a trip to Trinidad to see sea turtles haul out of the ocean and dig holes in the sand to lay sea turtle eggs. Show your support of sea turtles by wearing a CSTN hoodie, hat or t-shirt.

This field trip with CSTN is on my bucket list of places to visit. Trinidad has beaches that host one of the biggest nesting colonies of leatherback sea turtles globally with approximately 60% of leatherback turtles who forage in Canadian waters in summer months originating from the Trinidad nesting population (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). During nightly volunteer sessions, the field trip group will “assist with counting, measuring, and tagging endangered leatherback turtles” that arrive on the beach to lay their eggs (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). Training includes “sea turtle identification, data collection, and use of research equipment” with the focus on adult nesting females (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021).

The trip is based in the village of “Matura, a small, friendly, rural community in northeastern Trinidad” with CSTN research partner, Nature Seekers, and the Matura Beach Protected Area (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). “Trinidad is the southernmost island in the chain of Caribbean islands stretching from Florida to South America”, located 10 miles off the northeast coast of Venezuela, with the island enjoying a tropical climate year-round (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). Trinidad is rich in cultural diversity, including the music and food. The trip also allows for the learning of Trinidad’s natural environment through interaction with the guides and daytime trips to local “ecotourism establishments” (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021).

CSTN collaboratives with Nature Seekers on tropical sea turtle nesting beaches since its beginning and directly with Nature Seekers stretching back to 1999 (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). 100% of the cost of the trip goes to supporting the work of CSTN and grassroots partners in Trinidad (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). To learn more about CSTN working with leatherbacks on Matura Beach, please check out the CSTN blog (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021).

The trip is based in the village of “Matura, a small, friendly, rural community in northeastern Trinidad” with CSTN research partner, Nature Seekers, and the Matura Beach Protected Area (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). “Trinidad is the southernmost island in the chain of Caribbean islands stretching from Florida to South America”, located 10 miles off the northeast coast of Venezuela, with the island enjoying a tropical climate year-round (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). Trinidad is rich in cultural diversity, including the music and food. The trip also allows for the learning of Trinidad’s natural environment through interaction with the guides and daytime trips to local “ecotourism establishments” (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021).

CSTN collaboratives with Nature Seekers on tropical sea turtle nesting beaches since its beginning and directly with Nature Seekers stretching back to 1999 (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). 100% of the cost of the trip goes to supporting the work of CSTN and grassroots partners in Trinidad (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021). To learn more about CSTN working with leatherbacks on Matura Beach, please check out the CSTN blog (Canadian Sea Turtle Network, 2021).

When I do craft shows/markets I put up CSTN posters to bring attention to sea turtles. I have had conversations with fishermen, beach combers, other crafters, and others regarding sea turtles. I have found that sea turtles are favorably viewed by individuals, and they are interested in learning how to save them.

If you want to get involved to help conservation efforts of sea turtles, there are many ways to help these species who have lived on the planet for 150 million years (Natureseekers.org, n.d.) when dinosaurs roamed the planet (Welch, 2021). Contact CSTN to learn more about their mission in helping sea turtles.

Can you imagine the stories sea turtles tell their descendants throughout their existence? It would be unparalleled in relation to human history. Let’s dive into research, monitor, beach comb, beach patrol, find conservation initiatives, innovate, adapt, and help save sea turtles so they can continue swimming and surviving globally. Hope for sea turtles exists. Let’s take the time to help these precious species.

If you want to get involved to help conservation efforts of sea turtles, there are many ways to help these species who have lived on the planet for 150 million years (Natureseekers.org, n.d.) when dinosaurs roamed the planet (Welch, 2021). Contact CSTN to learn more about their mission in helping sea turtles.

Can you imagine the stories sea turtles tell their descendants throughout their existence? It would be unparalleled in relation to human history. Let’s dive into research, monitor, beach comb, beach patrol, find conservation initiatives, innovate, adapt, and help save sea turtles so they can continue swimming and surviving globally. Hope for sea turtles exists. Let’s take the time to help these precious species.

Further Resources

Hypothermic turtle revived after rescue from Bay of Fundy shore, shipped to Bermuda

Meet the dog who can find rare sea turtle nests at a shocking success rate

Sea turtles are surviving—despite us

Scotti, an endangered sea turtle found in N.S., back in Bermuda

Meet the dog who can find rare sea turtle nests at a shocking success rate

Sea turtles are surviving—despite us

Scotti, an endangered sea turtle found in N.S., back in Bermuda

Canadian Sea Turtle Network

Canadian Sea Turtle Network

2037 Kline St, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3L 2X4

(902) 423-6224

[email protected]

CSTN Blog CSTN Events CSTN Facebook Page

CSTN Store Donate to CSTN Learn with CSTN

CSTN Ambassador Program

(Credit: Canadian Sea Turtle Network)

2037 Kline St, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3L 2X4

(902) 423-6224

[email protected]

CSTN Blog CSTN Events CSTN Facebook Page

CSTN Store Donate to CSTN Learn with CSTN

CSTN Ambassador Program

(Credit: Canadian Sea Turtle Network)

Credit: Canadian Sea Turtle Network

| | |

Credit: Canadian Sea Turtle Network

Credit: Left: Canadian Sea Turtle Network website QC code; Right: Map of CSTN, Halifax, NS

References

Auld, A. (2023, November 28). A rare survivor: Team Rescue effort ends in spectacular triumph for Beached Sea Turtle. Dalhousie News. https://www.dal.ca/news/2023/11/28/scottie-sea-turtle-rescue.html

Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., & Kaplan, S. (2008). The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting with

Nature. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1207–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02225.x

Brown, E. A. (2023, September 19). Meet the dog who can find rare sea turtle nests at a

shocking success rate. Animals. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/sniffer-dogs-conservation-sea-turtles-florida

Canadian Sea Turtle Network. (2017). Sea Turtles of Atlantic Canada.

Canadian Sea Turtle Network. (2021, August 13). Canadian sea turtle network. https://seaturtle.ca/

Canadian Sea Turtle Network. Facebook. (2023, November 23). https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100080049500472

Casale, P. (2011). Sea turtle by-catch in the Mediterranean. Fish and Fisheries (Oxford, England),

12(3), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00394.x

CSTN. (n.d.). This is not just a store. CSTN. https://my-site-109448-104154.square.site/

Guardian News and Media. (2023, November 27). The nature cure: How time outdoors

transforms our memory, imagination and logic. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/nov/27/the-nature-cure-how-time-outdoors-transforms-our-memory-imagination-and-logic

Hays, G. C., & Hawkes, L. A. (2018). Satellite Tracking Sea Turtles: Opportunities and Challenges to Address Key Questions. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00432

Hays, G. C., Morrice, M., & Tromp, J. J. (2023). A review of the importance of south-east Australian waters as a global hotspot for leatherback turtle foraging and entanglement threat in fisheries. Marine Biology, 170(6). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-023-04222-3

IUCN. (n.d.). Red list assessments: IUCN-SSC marine turtle specialist group.

IUCN. https://www.iucn-mtsg.org/statuses

Kamrowski, R. L., Sutton, S. G., Tobin, R. C., & Hamann, M. (2014). Potential Applicability

of Persuasive Communication to Light-Glow Reduction Efforts: A Case Study of

Marine Turtle Conservation. Environmental Management (New York), 54(3), 583–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-014-0308-9

Leatherback turtles feed on jellyfish in Canadian waters off Nova Scotia. YouTube. (2018,

July 24). https://youtu.be/weE1vRvPdEk?si=PLGbIub2iRk6UT-h

McLean, M., Warner, B., Markham, R., Fischer, M., Walker, J., Klein, C., Hoeberechts,

M., & Dunn, D. C. (2023). Connecting conservation & culture: The importance

of Indigenous Knowledge in conservation decision-making and resource management of migratory marine species. Marine Policy, 155, 105582-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105582

Muñoz, C. C., Hendriks, A. J., Ragas, A. M. J., & Vermeiren, P. (2021). Internal and Maternal Distribution of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Sea Turtle Tissues: A Meta-Analysis. Environmental Science & Technology, 55(14), 10012–10024. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c02845

Nahill, B. (Ed.). (2021). Sea turtle research and conservation: lessons from working in

the field. Elsevier.

National Geographic. (n.d.). Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle: National geographic. Animals. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/reptiles/facts/kemps-ridley-sea-turtle

Scheelings, T. F. (2023). Reproduction in Sea Turtles, a Review. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery, 33(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.5818/JHMS-D-22-00041

Sea Turtles. Natureseekers.org. (n.d.). https://natureseekers.org/sea-turtles/

Tutton, M. (2023, November 24). Hypothermic Turtle revived after rescue from Bay of Fundy

Shore, shipped to bermuda. CTVNews Atlantic. https://atlantic.ctvnews.ca/more/hypothermic-

turtle-revived-after-rescue-from-bay-of-fundy-shore-shipped-south-1.6659448

van Putten, I., Cvitanovic, C., Tuohy, P., Annand-Jones, R., Dunlop, M., Hobday, A.,

Thomas, L., & Richards, S. (2023). A focus on flatback turtles: the social

acceptability of conservation interventions in two Australian case studies. Endangered Species Research, 52, 189–201. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01273

Welch, C. (2021, May 3). Sea turtles are surviving-despite US. Animals.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/sea-turtles-are-surviving-

despite-threats-from-humans-feature

Wilson, P., Pattiaratchi, C., Whiting, S., Ferreira, L., Fossette, S., Pendoley, K., &

Thums, M. (2023). Predicting core areas of flatback turtle hatchlings and potential

exposure to threats. Endangered Species Research, 52, 129–147. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01269

Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., & Kaplan, S. (2008). The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting with

Nature. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1207–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02225.x

Brown, E. A. (2023, September 19). Meet the dog who can find rare sea turtle nests at a

shocking success rate. Animals. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/sniffer-dogs-conservation-sea-turtles-florida

Canadian Sea Turtle Network. (2017). Sea Turtles of Atlantic Canada.

Canadian Sea Turtle Network. (2021, August 13). Canadian sea turtle network. https://seaturtle.ca/

Canadian Sea Turtle Network. Facebook. (2023, November 23). https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100080049500472

Casale, P. (2011). Sea turtle by-catch in the Mediterranean. Fish and Fisheries (Oxford, England),

12(3), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00394.x

CSTN. (n.d.). This is not just a store. CSTN. https://my-site-109448-104154.square.site/

Guardian News and Media. (2023, November 27). The nature cure: How time outdoors

transforms our memory, imagination and logic. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/nov/27/the-nature-cure-how-time-outdoors-transforms-our-memory-imagination-and-logic

Hays, G. C., & Hawkes, L. A. (2018). Satellite Tracking Sea Turtles: Opportunities and Challenges to Address Key Questions. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00432

Hays, G. C., Morrice, M., & Tromp, J. J. (2023). A review of the importance of south-east Australian waters as a global hotspot for leatherback turtle foraging and entanglement threat in fisheries. Marine Biology, 170(6). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-023-04222-3

IUCN. (n.d.). Red list assessments: IUCN-SSC marine turtle specialist group.

IUCN. https://www.iucn-mtsg.org/statuses

Kamrowski, R. L., Sutton, S. G., Tobin, R. C., & Hamann, M. (2014). Potential Applicability

of Persuasive Communication to Light-Glow Reduction Efforts: A Case Study of

Marine Turtle Conservation. Environmental Management (New York), 54(3), 583–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-014-0308-9

Leatherback turtles feed on jellyfish in Canadian waters off Nova Scotia. YouTube. (2018,

July 24). https://youtu.be/weE1vRvPdEk?si=PLGbIub2iRk6UT-h

McLean, M., Warner, B., Markham, R., Fischer, M., Walker, J., Klein, C., Hoeberechts,

M., & Dunn, D. C. (2023). Connecting conservation & culture: The importance

of Indigenous Knowledge in conservation decision-making and resource management of migratory marine species. Marine Policy, 155, 105582-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105582

Muñoz, C. C., Hendriks, A. J., Ragas, A. M. J., & Vermeiren, P. (2021). Internal and Maternal Distribution of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Sea Turtle Tissues: A Meta-Analysis. Environmental Science & Technology, 55(14), 10012–10024. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c02845

Nahill, B. (Ed.). (2021). Sea turtle research and conservation: lessons from working in

the field. Elsevier.

National Geographic. (n.d.). Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle: National geographic. Animals. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/reptiles/facts/kemps-ridley-sea-turtle

Scheelings, T. F. (2023). Reproduction in Sea Turtles, a Review. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery, 33(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.5818/JHMS-D-22-00041

Sea Turtles. Natureseekers.org. (n.d.). https://natureseekers.org/sea-turtles/

Tutton, M. (2023, November 24). Hypothermic Turtle revived after rescue from Bay of Fundy

Shore, shipped to bermuda. CTVNews Atlantic. https://atlantic.ctvnews.ca/more/hypothermic-

turtle-revived-after-rescue-from-bay-of-fundy-shore-shipped-south-1.6659448

van Putten, I., Cvitanovic, C., Tuohy, P., Annand-Jones, R., Dunlop, M., Hobday, A.,

Thomas, L., & Richards, S. (2023). A focus on flatback turtles: the social

acceptability of conservation interventions in two Australian case studies. Endangered Species Research, 52, 189–201. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01273

Welch, C. (2021, May 3). Sea turtles are surviving-despite US. Animals.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/sea-turtles-are-surviving-

despite-threats-from-humans-feature

Wilson, P., Pattiaratchi, C., Whiting, S., Ferreira, L., Fossette, S., Pendoley, K., &

Thums, M. (2023). Predicting core areas of flatback turtle hatchlings and potential

exposure to threats. Endangered Species Research, 52, 129–147. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01269

#CSTN #seaturtles #turtles #endangeredspecies #leatherback #greenturtle #oliveridley #kempsridley #flatback #hawksbill #loggerhead #novascotia #novascotialife #sustainability #AcademicTwitter #communitysupport #volunteering #beach #beachcombing #beachlife #nature #naturelover #vulnerable #conservation #getouside #getinvolved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed